By Eli Lake & Josh Rogin – Bloomberg View

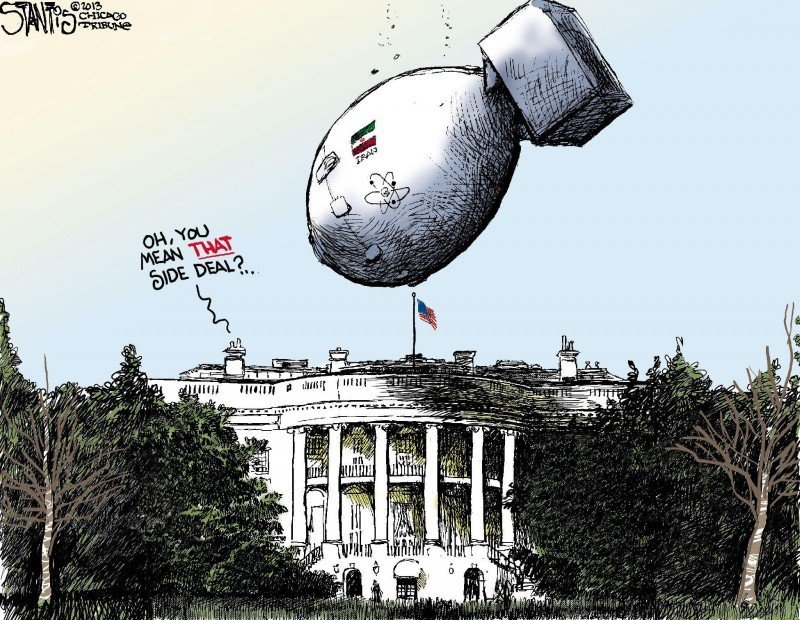

For anyone hoping a nuclear deal with Iran might stop the Tehran government from destabilizing the Middle East or free its political prisoners, the Obama administration has some bad news: It’s just an arms control agreement.

As details of a proposed pact leaked out of the Geneva talks Monday, administration officials told us they will ask the world to judge any final nuclear agreement on the technical aspects only, not on whether the deal will spur Iranian reform.

“The only consideration driving what is part of any comprehensive agreement with Iran is how we can get to a one-year breakout time and cut off the four pathways for Iran to get enough material for a nuclear weapon, period,” said State Department spokeswoman Marie Harf. “And if we reach an agreement, that will be the basis upon which people should judge it — on the technical merits of it, not on anything else.”

When asked if the State Department would argue the benefits of any deal in part by saying it would help Iran’s president, Hassan Rouhani, against his country’s hard-liners and therefore promote reforms, Harf said: “This is absolutely ridiculous.”

This is a long way from the grand aspirational sentiments expressed by President Barack Obama back in 2009, when he announced his intention to engage Iran. Obama, speaking on the Persian new year celebration of Nowruz, said he wanted “the Islamic Republic of Iran to take its rightful place in the community of nations.”

Back then, many advocates for engagement argued that the nuclear deal could unlock the key to moderating Iran’s rogue behavior.

Iran, however, spurned Obama’s outstretched hand. A few months after the Nowruz message, the regime conducted widespread arrests of people who had protested a presidential election they claimed their country’s supreme leader had stolen. And in 2011, Iran stuck with Syria’s dictator, Bashar al-Assad, as he declared war on his own people with barrel bombs and chemical weapons. This year, Iran’s fingerprints are all over the overthrow of the pro-American government in Yemen and violent Shiite militias unleashed in Iraq.

Given that track record, it’s easy to understand why the Obama administration would now focus on the nonproliferation benefits of an Iran deal alone. A senior official told us that the White House’s arguments would not suggest a “broad rapprochement” with Iran, and would “make clear that any deal will not lessen in any way our concerns about Iran’s regional policies.”

Yet many of the White House’s allies will make a markedly different case for an Iran deal, should one come about. Several advocates told us Monday that one of the advantages of an accord is that any phased lifting of sanctions, combined with a decrease in hostility between Iran and the country its leaders call “the great Satan,” could help the country’s moderates and over time lead to reforms in the world’s leading state sponsor of terrorism.

That’s a potentially powerful argument for a pact that will likely face considerable opposition from Republicans and even many Democrats, who worry that Obama’s envoys will let Iran keep too much of the infrastructure it would need to break out and make a weapon.

“You would hope that this deal could lead to changes to the Iranian regime’s behavior and even changes in the Iranian regime,” said Joe Cirincione, president of the Ploughshares Fund and a member of the State Department’s International Security Advisory Board. “Anybody who’s been doing national security for more than five years know there’s no guarantees, but there’s a very good chance it will it will weaken the hardliners in Iran (and) allow Rouhani to move forward with the social reforms he has been talking about.”

Cirincione’s Ploughshares Fund has given money to a wide array of groups advocating for a nuclear deal, many of which are aligned with the Democratic Party. These include the Arms Control Association, the Council for a Livable World, the Center for American Progress, the Institute for Policy Studies and the Israel-affairs group J Street.

Gary Samore, who was the White House coordinator for arms control and weapons of mass destruction in Obama’s first term, echoed Cirincione.

“A nuclear agreement that lifts sanctions and reduces tensions with Iran will advantage the moderates and make it more likely that in the period of the agreement Iran will become a status quo power and be less interested in developing nuclear weapons,” Samore told us.

He acknowledged that there was no guarantee of such changes, but said the risk of Iran acquiring a nuclear weapon was greater in the absence of a deal than with one.

This issue has become all the more pertinent with reports from Geneva that the outlines of a 10- or 15-year nuclear deal with Iran would gradually lift some of the restrictions on the program in the final years, if Iran was meeting its obligations. The Associated Press reported that negotiators in the six-party talks were discussing the prospect of allowing the Iranians to keep 6,500 centrifuges for enrichment as a compromise and operate more of them over time if they were living up to the terms of the deal.

That position in some ways represents an erosion of the U.S. position over time. While Hillary Clinton in 2011 floated the idea that a compromise would allow some enrichment of uranium, most observers assumed any deal would require Iran to dismantle most of the nuclear infrastructure it built up in the last decade in defiance of U.N. Security Council resolutions.

The contention from advocates such as Samore and Cirincione, however, has the advantage of turning U.S. concessions on sanctions into an advantage. This echoes the way Obama argued efforts to ease the embargo on Cuba gave the U.S. more leverage to push for democracy inside the island.

A similar line of thinking was promoted in the 1990s, when the U.S. struck a deal with North Korea to put severe limits on its nuclear program in exchange for sanctions relief. Of course, Pyongyang only increased its internal repression and nuclear ambitions.

Cirincione insisted that Iran is different than North Korea because it is a more diverse and vibrant society with a reform movement that enjoys some level of public tolerance. He also said that both the hard-liners and the reformers there believe that a nuclear deal with the West could pave the way for greater social and political reforms.

“A nuclear deal is going to be greeted as near-euphoria for the Iranian people because they see it as a beginning of the reforms,” he said. Then he warned: “Just because people go out on the streets and protest, that doesn’t mean good things will happen. I mean, look at Egypt.”

Iran’s pro-democracy green movement is today in shambles. Its two leaders — Mehdi Karroubi and Mir Hossein Mousavi — have been under house arrest since 2010, despite promises from Rouhani during his electoral campaign in 2013 to free dissidents.

Nonetheless, Rod Sanjabi, the executive director of the Iran Human Rights Documentation Center, said he favored lifting sanctions and easing tensions from a human-rights perspective.

“Short term, who can tell how the government will react? Who can tell how the security of a nuclear deal and better relations with the West will affect the government’s relation to the opposition or civil society in general?” he said. “Those things are certainly true. It’s also true as long as the middle class is living hand to mouth, it will not be able to push for the kinds of changes we would like to see.”

It’s a potentially powerful argument. And it’s one the White House and the State Department will not be making.

COMMENTS