By former Foreign Secretary of Britain David Miliband

With every week that goes by in the Syria crisis, hundreds more lives are lost, policy options narrow and the chances of post-conflict stability grow worse. What started as a demand for internal reform has become a regional conflagration. Foreign fighters from across the Middle East and North Africa are pouring into Syria to train and fight, while refugees are flooding by the hundreds of thousands into Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq and Turkey.

The Western political debate has focused on military options and the arguments are complex and finely balanced. But no one believes that under any scenario the war will end quickly.

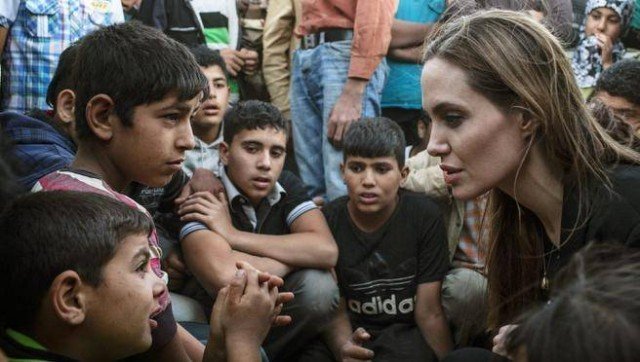

Meanwhile, the gap between humanitarian need and international response grows by the day. My three days in Jordan last week do not provide a complete picture, but they do allow for stories to be combined with data to reveal a deeply alarming situation.

Inside Syria, the International Rescue Committee has talked with refugees who reported that life-threatening shortages of medicines and food and fuel shortages are a daily reality. Doctors told me of colleagues and relatives who have been targeted, and killed, in the war. There are allegations of truly horrific human rights abuse. Nearly seven million Syrians are living in desperate conditions.

In addition to nearly 100,000 killed inside Syria (and countless more dying for lack of medical help), close to a third of the Syrian population has been displaced within the country or beyond. Refugee numbers in Jordan amount to over 10 percent of the population. In Lebanon the figure is closer to 14 percent.

So the strain on communities hosting refugees is tangible. There are refugee camps in Jordan, Iraq and Turkey, but across the region the large majority of refugees are fending for themselves in urban areas.

I sat with four families in the two-room apartment (plus kitchen) they share in Mafraq, in northern Jordan, with some 15 children. There is immense pressure on local services, from education to garbage disposal. Rents are being pushed up by landlords who know that there is U.N.-sponsored cash assistance available. Children are not allowed out.

At an I.R.C. clinic for Syrian refugees, I heard mothers and widows talk about dead husbands and sons. A Bedouin family explained that the head of the family had been shot by a sniper while lined up for bread. Violence against women, detailed in I.R.C.”™s January report “Syria: A Regional Crisis,” is rife.

This humanitarian toll is now as much a part of the geopolitics as the balance of military power. The scale of killing has created sectarian reprisals, not just in Syria but in Lebanon and Iraq. Meanwhile, the extent of refugee flows is itself a source of destabilization. And under any scenario, there are many more refugees to come ”” not least the 250,000 to 300,000 Syrians living up against the Jordanian border.

The United States and European countries have made substantial aid commitments, notably the $300 million tranche of aid announced by President Obama last month. It is also the case that there is significant money from Gulf countries: Saudi Arabia, Qatar and United Arab Emirates.

But the mismatch between need and aid is, according to the United Nations, massive. The public in Western countries has been noticeably more reluctant to give money than in previous crises. Yet my trip to Jordan convinced me that practical steps can be taken to move from meeting a fraction of total need to meeting much more of it.

First, their supporters must put pressure on the government in Damascus and the rebels to adhere to international laws and norms for the protection of civilians in the conduct of war. Obama spoke about this in his speech to the National Defense University, and his call should be supported by all countries.

Second, there is a responsibility on both sides to promote free access for humanitarian help, across the lines between government and rebel-held areas. The blockages on humanitarian access are severe ”” and costing lives.

Third, there is scope for cross-border help for distressed communities, from all the neighbors. Brave Syrians are risking their own lives, and more of them are willing to do so, but they need funds for medical aid and food.

Fourth, neighboring states need help to cope with refugee flows. This is basic investment in their resilience.

These measures are not just a matter for  Western donors and the Western public. There needs to be a major change in our engagement if we are to stanch a regional crisis that is a human tragedy on a monumental scale. Millions of lives are at stake, as well as the values and interests of the West.

David Miliband is a former foreign secretary of Britain who in September will become president and C.E.O. of the International Rescue Committee.

COMMENTS